Flotsam, Jetsam, Liam - Issue #13

“The world spins. We stumble on. It is enough.”

Pour one out for Martijn de Kuijper. The Dutchman found himself absorbing a whole bunch of Twitter content in 2015 when it dawned on him that email newsletters would allow for more depth and better audience curation. He founded Revue, hired five others, raised a modest six figure sum, and quietly went about creating a very pleasant writing and publishing experience for amateur writers like yours truly from the friendly confines of Utrecht.

In early 2021, Twitter came calling, eager to emulate Substack’s explosive growth with a newsletter service of their own that easily integrated with the platform. de Kuijper cashed in and suddenly found himself working as a Product Manager at the company that had originally inspired his venture.

Then, Overlord Musk lit $44 billion on fire, and as part of his crusade to enable more free speech, chose to sunset Revue for good earlier this year. I sensed the writing might be on the wall when my World Cup preview newsletter went straight to everyone’s spam back in November (although some part of me wondered whether it was a cosmic sign that this drivel I scribble had found its rightful home).

As of February, de Kuijper has reason to believe he is out of a job after being locked out of his email at Twitter alongside 200 others, but has apparently received no additional communication from the company since. Life comes at you fast.

Try as they might to wipe the previous issues of Flotsam, Jetsam, Liam from the record, I painstakingly re-formatted, re-hyperlinked and copied the dozen previous editions over to Substack, which currently finds itself in a feud of its own with Twitter.

Long story short, same flotsam, just making its way to a different Great Pacific Garbage Patch. Thank you for staying along for the ride.

2022 Adventures and Their Vestiges

I need no invitation to travel while I’m young, and actually came away from 2022 feeling as though I probably need to spend a few more weekends staying local to get the most out of living in DC (adherence to that protocol soon to be derailed by eight sickeningly delightful humans tying the knot this summer).

Last year did bring me to necks of all sorts of unfamiliar woods, with exotic bird songs and peculiar plant species as it were, that sparked five big questions for me.

Tri-Cities, WA - What “good jobs” might be wolves in sheep’s clothing?

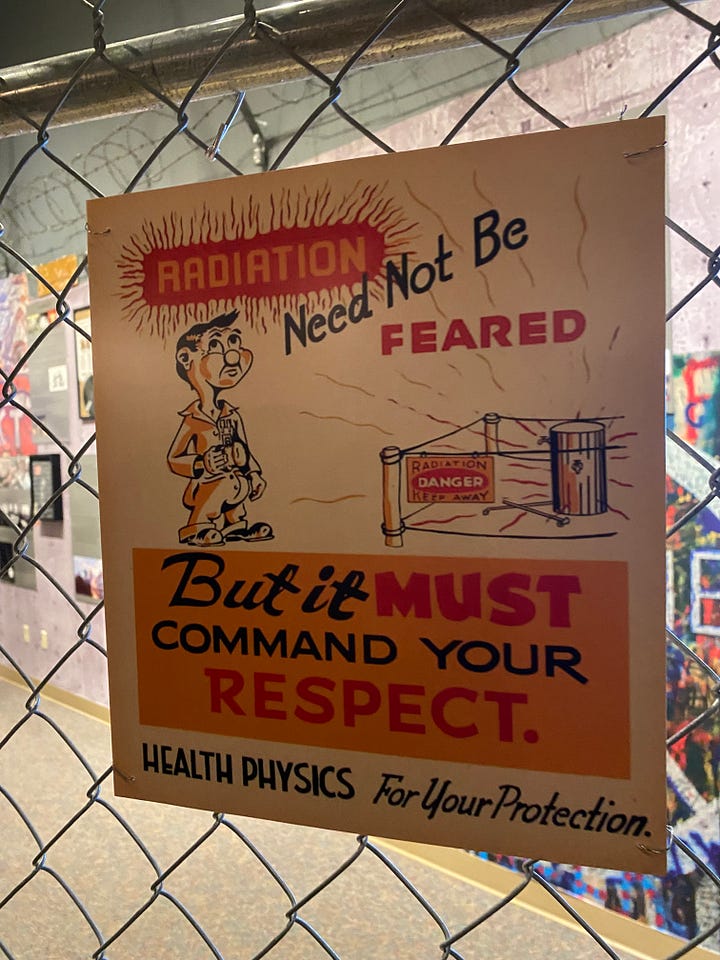

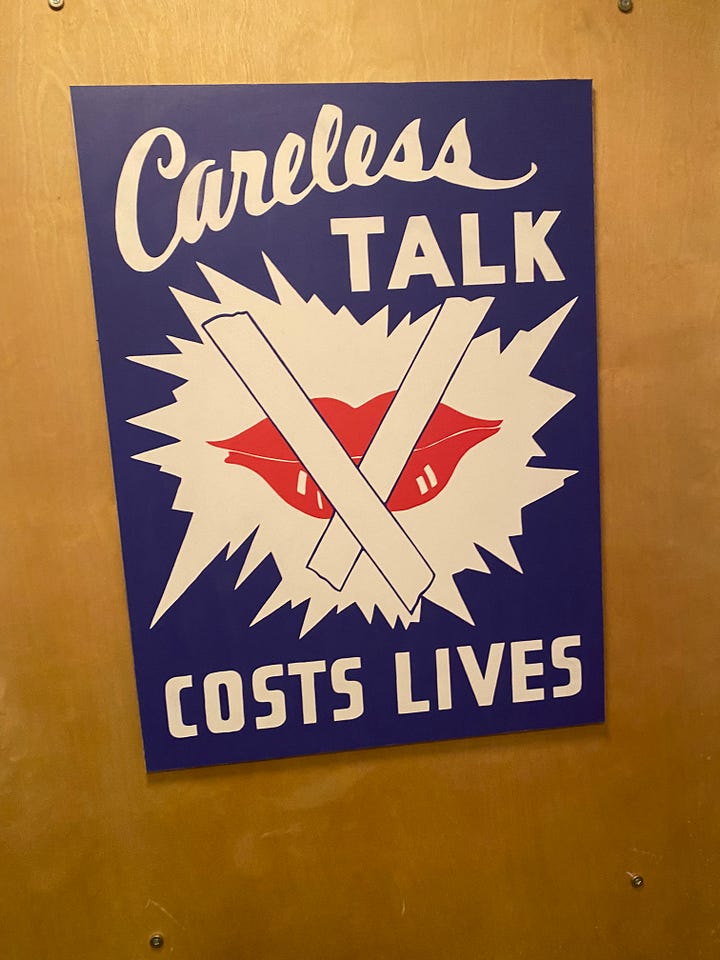

At the confluence of three rivers - the Snake, Yakima and Columbia - lies the Tri-Cities of Central Washington State: Pasco, Richland and Kennewick. Today, their school districts are early adopters of Hazel Health’s teletherapy services (prompting my visit), but the metro region’s growth began in earnest in 1943 when the War Department went in search of “a remote, sparsely populated, easily defensible, geologically stable site with plenty of cool water, abundant energy from hydropower dams, and a moderate climate in order to build plutonium production reactors in secret”. Up went the Hanford site and out went several displaced Native tribes as government contracted firms went about recruiting workers to join a vague Pacific Northwest Construction Project. Accordingly to one pamphlet:

“There’s a job for you at Hanford. It’s not a short job and it’s not a small job. We can’t tell you much about it because it’s an important war job, but we can tell you it’s new heavy industrial plant construction.”

Placated by decent wages, barrack housing, and a sense they were fulfilling their patriotic duty, 45,000 workers descended upon Central Washington to produce the plutonium in the bomb dropped on Nagasaki. Fewer than 1% of them knew that was what they’d been summoned there to do until after Truman made the call.

No longer actively producing plutonium, Hanford now stands as the site of the largest environmental cleanup project in the world due to chemical and radioactive contamination.

I don’t know of any current big government schemes to coax unsuspecting citizens into nuclear war crimes, but the premise of getting swindled into a job that alleges prestige, relative comfort, and higher purpose yet causes harm doesn’t feel lost to the annals of history.

Some of big tech’s luster may be slowly fading, but the perception persists that working at a FAANG is a golden ticket to the good life. It’s become harder to ignore the pestilent externalities of that good life: a tech enabled youth mental health crisis, a sprinkle of democratic unraveling, a dash of workers’ rights corroding, and a garnish of exploitative cobalt mining extraction.

Other modern snake oils might be more self destructive than societally ruinous, but multilevel marketing schemes have proven adept at preying on new / stay at home moms under the guise of female empowerment, and the latest brand of pump and dump proposition championing financial freedom gave us the crypto bro archetype.

Six weeks later, my Manhattan Project rabbit hole would furrow deeper.

Los Alamos, NM - What if the world’s most brilliant scientists lived together and united around a common goal?

A hike around Bandelier National Monument with the guys on a perfect spring day is a phenomenal way to spend a day off, and if you’ve already made the trek out there, Los Alamos beckons just 12 miles away. So without any real intention of doing so, I found myself at the second of the Manhattan Project’s three primary sites in quick succession.

With the National Laboratory still alive and well, Los Alamos is idyllic and affluent today, but in the ‘40s, it must have been a tough sell. However brilliant of a theoretical physicist he was, J. Robert Oppenheimer’s ability to convince 6,000 people - encompassing the nation’s top scientists and their families - to relocate to a barren desert town to build a bomb while sworn to secrecy is astounding in its own right.

Fast forward to the 2020s, and Operation Warp Speed had a whiff of Los Alamos about it, revolutionary and timely American innovation under extreme pressure. Fanciful to suppose the brightest among us would run it back and all dutifully congregate in the desert, but with 600,000+ Americans on track to die of cancer this year and the Climate Emergency showing no signs of course correcting, what could such highly concentrated scientific genius accomplish today?

New Orleans, LA - Can I admire someone’s resolve and abhor their output?

Logan Roy - the gruff, megalomaniacal patriarch Brian Cox portrays in Succession - can’t hold a candle to the insatiable appetite for power Samuel Zemurray demonstrated throughout his lifetime, but I’d never heard of Sam the Banana Man until I took a solo-trip to New Orleans last May (Short aside: cities with some combination of ubiquitous live music, rich history, and a renowned culinary scene make for ideal solo vacation destinations).

While browsing the local history selection at a used book store in the French Quarter, I happened across The Fish that Ate the Whale: The Life and Times of America’s Banana King by Rich Cohen. The shopkeeper saw my intrigue and chimed in: “That guy? He donated his mansion. President of Tulane lives there now.” I had to know more. Payment was exchanged. Always be closing.

In the late nineteenth century, Zemurray emigrated as a boy from modern day Moldova to Selma, Alabama. As bananas were just starting to infiltrate the American food scene as an exotic good, he’d frequent the docks in Mobile and study the handling of the fruits as they were transferred onto ships and railroads. Where others saw product ripening too fast to be able to bring to market, he saw opportunity. He fancied himself to roll into towns along the train lines and sell ripe bananas for a small profit after he’d bought them for a pittance. With each new crop, the race against time began again. In 1899, he sold 20,000 bananas. Within a decade, he was in his early thirties and selling over a million a year (Cohen, p. 24-25), and he settled down in New Orleans in 1905, with a wife and kids soon to follow.

Meanwhile, the old world, blue blood New Englanders who puppeteered the fruit trade at the time sought to consolidate their financial and land holdings (which spanned 212,349 acres across the Dominican Republic, Cuba, Jamaica, Costa Rica, Honduras and Colombia (Cohen, p. 46)) into an insurmountable monopoly called United Fruit. The company held a fleet of 115 ships, acquired increasingly large swaths of jungle across Central America to be hacked down and planted, and began a mass marketing campaign to have Americans adopt bananas into their breakfast routine that included handing the fruits to Ellis Island immigrants as they were welcomed to America (Cohen, p. 49).

Yet Zemurray maintained an edge in the industry by being more willing to get stuck in. He went and lived in Honduras, worked on the farms, killed snakes, bought beers for the workers, and buttered up government officials in person, winning favorable rates over United Fruit. His intimate knowledge of people and place meant he was uniquely positioned to disobey orders from US Secretary of State Philander Knox, who’d been conspiring with J. P. Morgan to refinance Honduras’ debt and loan the Honduran president $5 million in exchange for a duty on all imports. Zemurray simply recruited Manuel Bonilla, a deposed former Honduran president he’d befriended in New Orleans to head an insurgency, covertly hired a warship, bluffed that naval reinforcements were on their way, and forced a surrender. Bonilla stepped into the presidency and was happy to negotiate business concessions with his benefactor.

In 1929, economic conditions pushed Zemurray to make a deal to sell his company, Cuyamel, to the behemoth United Fruit he had been spiting as competition and retire. His stake was worth $30 million, and he agreed to a standard noncompete clause to “neither work for a rival nor start a new fruit company of his own” (Cohen, p. 119). But rather than go quietly into the night, Zemurray watched on as United Fruit floundered through the 1930s, and went back to the docks to understand the realities on the ground. When his findings were ignored by the company’s board, he crowdsourced the proxy votes he needed to fire the chairman and get himself elected president, declaring:

“You gentlemen have been fucking up this business long enough. I’m going to straighten it out” (Cohen, p. 143).

In his next act, his imposition of control over the national sovereignty of Central American countries reached a crescendo. United Fruit owned 70% of Guatemala’s private land and all of its infrastructure by 1942. Populist uprisings to fight back grew increasingly violent, and the newly elected government began calling for socialist rule, restoring power to the people.

As business conditions became gradually less favorable and new President Jacobo Arbenz won plaudits from his citizens for pushing to expropriate uncultivated land, the Banana Man cooked up yet another coup. Zemurray hired PR big whigs from the CIA to begin a “red-baiting” campaign to frame Arbenz as a communist and a threat to American national security. A few strategically placed articles in major publications convinced the State Department that Arbenz was importing weapons to arm a Communist resistance. Rather than force his poor country into war, Arbenz stepped down and left the country disgraced, hopping between countries who did not want to grant him asylum. His beloved daughter, actress Arabella Arbenz took her own life in 1965, sending him into an even more depressive tailspin. Six years later, he drowned in a bathtub with whiskey at his side (Cohen, p. 207).

There shouldn’t be room to feel anything other than horror and outrage at a man who exploited entire nation states for profit, ravaged their democratic processes and institutions, and left violent conflict and irreconcilable debts in his wake. Yet I begrudgingly confess that I’m enamored by the cowboy-esque, roll up your sleeves, stick-it-to-the-man bravado of Zemurray’s approach to life, and I’m curious what it feels like when the chip on one’s shoulder hasn’t been programmed to know when to it’s time to back down. Somehow New Orleans feels like the appropriate backdrop for this conundrum. Things there aren’t black and white; they’re purple, they’re green, they’re gold.

Bilbao, Spain - Is urban revitalization as simple as giving a city one show stopping attraction?

Through the 1980s, Bilbao was a gritty industrial port city, immensely proud of its Basque identity, but struggling to keep pace in with economic currents. Local authorities bet big that going all in on culture would usher in brighter days ahead, and found a willing partner in New York’s Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation. They turned to up-and-coming “starchitect” Frank Gehry to expand their museum footprint into Europe, and his sweeping, whimsical metallic riverfront stronghold opened its doors in 1997, coming in on budget at $89 million.

Fewer than five years later, the museum could claim to infuse $150 million into the local economy annually, to have created 4,000+ jobs, and to be the motivating factor behind 82% of tourist visits to the city. Suddenly, every downtrodden city wanted a taste of the Bilbao effect.

So far, replicating Bilbao and Gehry’s success has remained as elusive as the origins of the Basque language. Was the Guggenheim simply a case of right place, right architect, right time? Have cities become wary of fully handing the keys over to creatives in an era of contentious city council meetings, skyrocketing construction costs, and NIMBY-ism? Does a modern pysche raised on pop-up shop virality have the patience to let landmarks striving for timelessness flourish?

Even if more of an anomaly than an exemplar, Bilbao’s conviction in letting art and culture lead the way is something worth beholding.

Medellín, Colombia - Is urban revitalization as simple as building equitable transit?

Or perhaps the urban glow up elixir comes in the form of a cable car. My most outlandish digital nomad scheme yet brought me and five others to Colombia’s City of Eternal Spring last October. 30 years ago, Medellín was a playground for Pablo Escobar’s cartel empire and had the highest murder rate of any city in the world. Today, remote workers flock to its trendy coffee shops, bustling nightlife, and vividly green urban parks. A wander around the hip El Poblado neighborhood feels like you’ve stumbled upon a giant Rainforest Cafe for adults.

Such a stark transformation is no accident and requires persistent and visionary leadership. Set amidst the Andes, Medellín’s streets slope steeply between barrios, which for decades meant winding commutes, limited mobility and unchecked violence for residents of hilltop communities. In 2000, city authorities and community members came together to conceive of a cable car project that would link these disjointed neighborhoods. Newly elected mayor Luis Pérez and his successor Sergio Fajardo embraced the plan and its overarching goal of social inclusion, and saw its implementation through.

Now 30,000 locals take the wonderfully scenic route daily, and a street car system awaits riders as they reach the southernmost stop to scurry onwards to other corridors of the city. Small businesses and eateries dot the street corners surrounding the well-kept stations.

Medellín is a shining example of what can happen when leaders invest in historically overlooked people by hearing them out, connecting them to opportunity, and seeing to it that these commitments go beyond window-dressing and actually last. In addition to the Metrocable, the city has built entrepreneurship centers, stood up day care centers with teacher training programs, and invited civic participation in development project budget allocation.

Transit advocates love to cite Enrique Peñalosa, a two time mayor of Bogota, Colombia’s Capital city 260 miles from Medellín, who famously quipped that:

“An advanced city is not one where the poor own a car, but one where the rich use public transport.”

I appreciate the sentiment but worry it shifts the focus. Build services that advantage the disadvantaged, that work well for people who aren’t spoiled for choice. What might start as one less thing for them to have to worry about can quickly become a point of civic pride (and expand the customer base for hawkers of scrumptious tropical fruit ⬇️).